Characters and Strings… We have worked some with it so far, but just really putting the strings out there for the user to read and then reading in a single character or number.

I guess we will learn more about what you can do with strings in this chapter. I just watched some video saying that C++ didn’t have strings, so I’m a little confused though. But I hope everything will be more apparent after watching this chapter of the course.

Lecture 93: Section Overview

This section shows the legacy of C in C++. We will work with both C-style strings and C++-style strings and learn the difference between them

The instructor does advise us to use C++ strings, so I guess that C++ has some aces up its sleeve when compared to the older C. The instructor hints to C++ strings being objects, so I think that’s where some of the difference lies.

Lecture 94: Character Functions

The header-file cctype includes several functions for working with characters. You can test characters for several properties. For instance, you can check if the character is a letter or a digit, or if it’s lowercase or uppercase.

It also has functions for converting characters to lowercase or uppercase that are very handy.

I’m a little bit confused about these though since I used tolower() in the last section challenge, but I did not include the cctype header. I tried googling an answer for this but was unable to find any, so I’ve asked it in the Q&A-section for the video.

Lecture 95: C-Style Strings

C-style strings are just an array of characters in contiguous memory that is terminated by a null character. This means that a string uses at least one memory space more than is shown on screen since the last character is used by C++ to determine where the string ends.

This can lead to problems if you treat it like a regular array, as the termination character is a valid memory space and you won’t get any errors or warnings from the compiler if you try to change it.

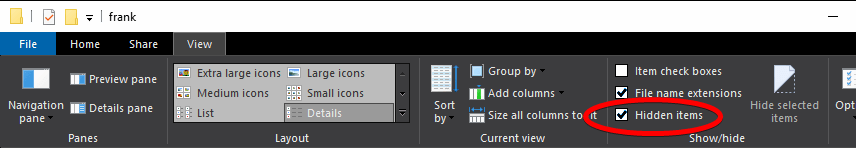

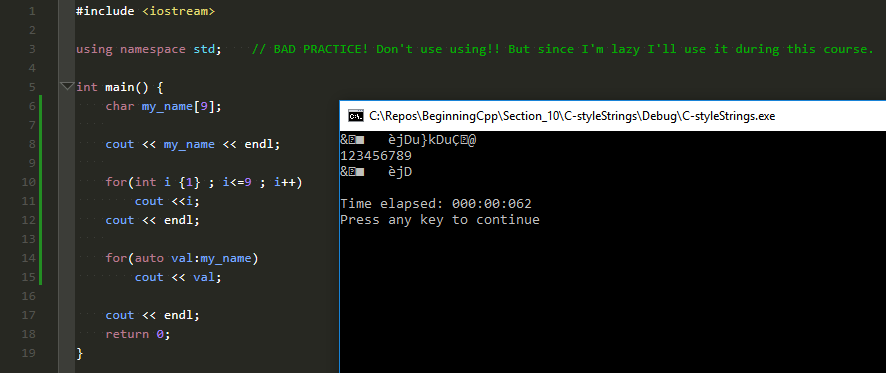

I made a small program showing what can happen if you don’t treat strings with care. I declared a char-array with 9 spaces and printed it. I then made two for loops to write out the numbers from 1 to 9, just to make it easier to see the characters, and then I printed each character by itself, looping through the array with a range-based for loop.

As you can see, the first string printed is much longer than the contents of the array, and that’s because there was no termination character inside the array. Had I been unlucky, the printout might have been much, much longer. It could also have ended on the first character. We just don’t know, as the contents of the array are undefined, precisely like Franks mentions in the video.

All C-style string functions in the cstring and cstdlib header files expect a null termination character, so it’s easy to see that you really must know what you do when working with these kinds of strings.

Programmers are smart, so they have known how to do this for a long time, but according to the instructor, many of these problems have been solved with C++ style strings. If you ask me, that sounds like the smarter thing, have the language take care of the behind the scenes stuff and let the programmer write code.

Lecture 96: Working with C-Style Strings

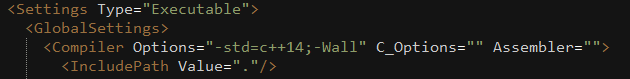

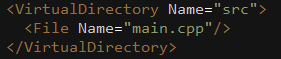

This video is going through examples on how you write code using C-style strings.

The instructor starts with some code showing the same I do above, but I think my example shows it better. 😊

But I’m not putting too much effort into this lecture, as the instructor told us to use C++ style strings mostly, so I’m waiting for that in the next part. But I guess it’s important to know this style since there’s probably a lot of code using strcpy() and strcmp() out there.

Lecture 97: C++ Strings

I watched a video from 2016 on YouTube that said C++ doesn’t have strings. And now I watch this video where Frank says that C++ has a large and complex string system. But maybe the first guy meant it wasn’t C++ proper since it’s in the STL. If you ask me though, it’s strange not seeing the Standard Template Library as a part of the language.

The C++ strings are object-based, so they fit into the style of C++ with the ability to use standard operators, member functions, etc. The easiest way to describe it is that it’s similar to using arrays or vectors. Both can more or less do the same, but one way is just keeping with using the old C-functions while the other way is using modern object-oriented programming.

That means that if you go the C++ way, your strings will behave like objects and have member functions that you use on them. When you declare a string variable, it’s always initialized for you, that means no risk of printing out garbage content to the screen if you forget to do it yourself. They are also dynamic in that they can grow and shrink in size. And maybe most important, they are safer to use. The functions use bounds checking, so less risk putting data into unknown memory space.

All in all, I will say that the looks easier and safer to use than C-style strings.

Lecture 98: Working with C++ Strings

Not surprisingly, this video is the instructor going through examples of using C++ style strings.

I must say it’s much clearer using C++ style than C-style strings. Probably because I don’t know C. But if you don’t know C, you have to agree it’s much easier to understand s1 = s2, than it is to understand strcpy(s2, s1).

Of course, in C-style, you know that you are copying strings, while in C++ you’re really not sure what types you’re assigning to each other. But with proper variable naming, that shouldn’t be a problem.

The instructor also shows us that other significant advantage of using the object-oriented style of C++. For instance, the functions do bounds checking for you, so you will never walk yourself out of a string using a poorly constructed loop.

Lecture 99-100: Section Challenge, Solution, and Quiz

A pretty cool challenge in this section. We’re essentially making a decoder ring. 😊

When you look at it, you might think that it must be very complicated to make an encoder and decoder. But then you look at the problem, break it down into parts and realize that it’s surprisingly easy. And C++ gives you all the tools you need to solve this problem.

All in all, the program I wrote was about 40 lines. I’m sure you can make it much shorter with some effort.

I loved this challenge since I’m a crypto nerd. Not like in the coin stuff but like secret messages. I think I’ll need to try to implement more ciphers in C++ and the Vigenère cipher for sure is something I need to work on.

Assignment 1: Challenge Assignment – Letter Pyramid

In this section, the instructor has also added a new kind of challenge or assignment for us. This time we need to get a string from the user, and we will then make a letter pyramid out of that string.

I learned that it’s important to break a problem into parts. At first, I was at a loss, but it got more manageable when I identified the three elements of the problem.

- Print padding

- Print the correct number of characters starting from the front

- Work back through the string from the position in 2 and print each character as you go

Then it was just a case of solving each small task, and it went somewhat easy from there.

It’s not the prettiest code, but it works. 🙂

What’s cool with this is that after you submit your solution, you get to see the same problem solved by three other students in the course. I must say that the answers I saw are wildly different. That also taught me a lot, since at least one of the students solved it in a brilliant way that I didn’t even remotely think about when I worked on the problem.

And as usual, go to GitHub for my attempt at writing some C++ code.